The Transformation of Lady Young

When I arrived in Trinidad for the first time I immediately got a good feeling about Lady Young, based on nothing more than driving up the roadway that bears her name in back of the Hilton Hotel. (That scenic overlook! I thought I was in the south of France!)

When I arrived in Trinidad for the first time I immediately got a good feeling about Lady Young, based on nothing more than driving up the roadway that bears her name in back of the Hilton Hotel. (That scenic overlook! I thought I was in the south of France!)

It turns out I was not alone. Even V.S. Naipaul, who rarely had a good word to say about Trinidad, felt his mood elevated by a trip up the hill. In “The Middle Passage” (1962) he put it this way: “You drive up to the new Lady Young Road, and the diminishing noise makes it seem cooler. You get to the top and look out at the city glittering below you . . .” (This must have been at night.)

To have a road named after her I figured Lady Young must have been the wife of a colonial governor and in that regard I was correct – she was married to Sir Hubert Young who ruled Trinidad with an iron grip during World War II.

Lady Young, on the other hand, I pictured as a model of femininity, offsetting the governor's harshness, but here I was much mistaken. In real life she was a bold, broad-shouldered woman who led a life of action and adventure. During World War I she drove a Red Cross ambulance in France. In the early 1930's, with three young children at home, she decided to take flying lessons and went on to earn a reputation as a daring bush pilot in southern Africa. (In the movie she would be played by Kate Winslet.) She was not at all ladylike. In her four years in Trinidad she showed herself to be impulse driven, easily irked, and, like her husband, a bit of a bully.

Sir Hubert was brought to Trinidad in 1938 to deal with the labour unrest that resulted in bloody riots the year before – twelve people shot dead by police. The colonial office felt he was up to the task because of his earlier success in breaking a strike by copper miners in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) – also with the use of deadly force.

His reputation preceded him to Trinidad. Prior to his arrival, labour leaders, led by Capt. A.A. Cipriani, marched through the streets of Port of Spain with signs reading, “WARM WELCOME SIR ‘HITLER’ YOUNG”, “BREAD, NOT BULLETS” and “TRINIDAD IS NOT RHODESIA”.

The signs were the work of a young British writer named Arthur Calder-Marshall who was in Port of Spain gathering material for a book. It came out the following year and was called, “Glory Dead” (as in, “Glory dead when white man come.”) In the book, Calder-Marshall wrote this:

“Apart from the sponge, the tout and the trickster, Trinidadians take no patronage. They speak to you on equality . . . That is what some Government officials, who have served in Rhodesia, find it hard to stomach. In Rhodesia the simple native is grateful and respectful towards an official in whose good faith he believes. But the Trinidadian has had a long history of broken promises, of cruel oppression and calculated neglect. He is a sophisticated type. His distrust is never far away.”

The distrust was deepened by one of the governor’s first official acts – the allocation of $48,000 in public funds for the refurbishment of Government House. It was an enormous sum (the equivalent of over $1M US in 2025) at a time when conditions in Trinidad were dire. It was probably Lady Young who called for many of the upgrades.

In response the calypsonian Atilla the Hun captured in song what many people were thinking when he wrote “What A Vote.” It went like this:

“Forty-eight thousand dollars, take it from me

To repair Government House is an absurdity.

The expenditure is morally bad

When there is so much starvation in Trinidad.”

The song was promptly banned which only added to its impact.

It was against this unforgiving backdrop that Lady Young set about creating new lines of discontent based on nothing more than the prickliness of her own personality. She quickly came to feel unappreciated, even rejected, by her own people – the white British establishment. Her paranoia mounted and finally on 10th March, 1940 she couldn't take it any longer. Dipping her pen in bile she dashed off a letter to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Malcolm McDonald, a letter so harmful to her own cause that I suspect she was in an altered state when she wrote it.

The letter began this way:

“Unfortunately as you know matters have not improved. It is all too stupid and in the middle of a War, or arising out of a War is too deplorable. Unfortunately also, nothing much that we can do will mend matters, as these people and the whole section – a small and vehement one they come from, have not even had manners they have no conception of manners, loyalty, or any other civilized virtue. They simply don’t live in the same box as ordinary human beings, one cannot calculate what any of their reactions are; they are as strange and remote morally as the Africans and low Caste Indians who have, as everything tends to sink, – much influenced the whole trend of life in these islands.”

IN THESE ISLANDS! OOF! When I first came across this excerpt (in a book) there was no context. I wondered – what “matters” was she talking about? Who were “these people”? I assumed she must have been referring to anti-colonial activists like Capt. Cipriani and Albert Gomes – her natural adversaries. But no. It turned out her chief nemesis was drawn from the cream of Trinidadian society – an Anglo/Scottish woman named Martha Eunice Simpson. Her family owned the immensely valuable Aranjuez Estate in San Juan. Her father had been mayor of Port of Spain.

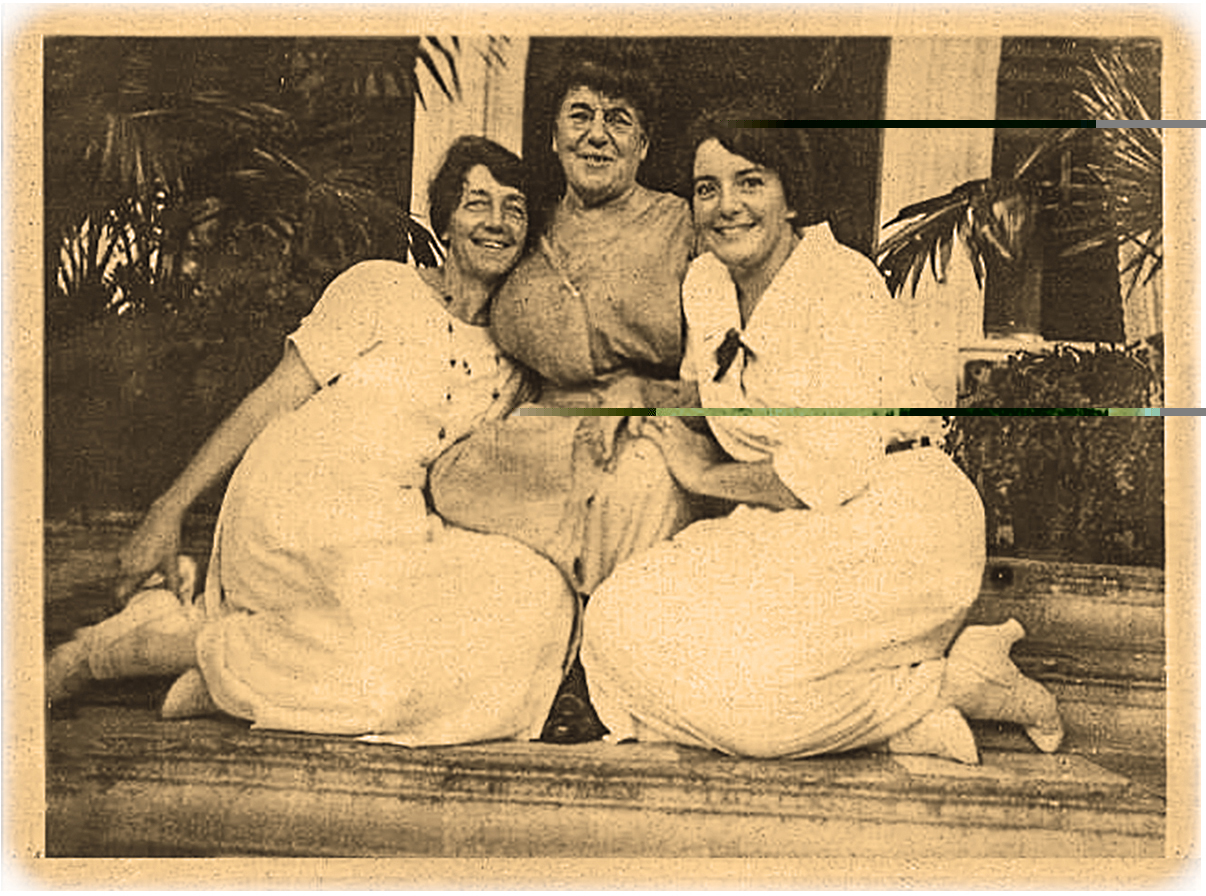

Photo courtesy of Robert Alexander Gordon Siegert.

The vendetta between Lady Young and Mrs Simpson began innocently enough. In the summer of 1939 Lady Young founded a chapter of the British Red Cross Society in Trinidad, drawing on her experience as a Red Cross nurse. As was her wont, she demanded total deference from everyone in getting her project up and running. In her mind she was the Red Cross.

About a month later the war broke out. Mrs Simpson quickly recruited four of her friends and formed a group, calling it the “Ladies’ Shirt Guild” whose purpose was to make articles of clothing for the war relief effort. She first approached a staff member at the Red Cross about joining forces but came away feeling there was too much red tape at the Red Cross – for one thing, patterns had to be pre-approved in London. So she decided to work independently, just as she had done during World War I. How could anyone find fault with that? Meanwhile, Lady Young was in Tobago and knew nothing about it.

The guild members were some of the most prominent women in the colony, including Dora Gilchrist and Edna Gordon. Dora was the wife of Trinidad’s chief justice, Edna a member of the fabulously wealthy Gordon clan. As a leading historian has pointed out, ladies of this social class “did no housework, never marketed, and rarely cooked.”

But, in times of trouble, they sewed. On 22nd September Mrs Simpson wrote directly to Queen Elizabeth offering to send articles of clothing to Buckingham Palace and received an enthusiastic letter of thanks in reply. This was big news in Port of Spain as it was whenever the royal family took notice of Trinidad. On 5th November the GUARDIAN printed the letter from the palace under the headline: “THE QUEEN THANKS TRINIDAD CLUB”. (See below)

Clipping from the front page

of the TRINIDAD GUARDIAN

When Lady Young saw the letter she went ballistic. Mrs Simpson and her informal group had stolen the spotlight away from her and the Red Cross! It was a situation that called for restraint, but Lady Young preferred steamroller tactics. At a meeting at Government House on 9th November, 1939 Lady Young, accompanied by her husband, berated Mrs Simpson for writing to the queen behind her back and tried to browbeat her into dissolving the guild and falling into line with the Red Cross relief effort.

Major Geoffrey Hugh Simpson, OBE

The collar pin is the

WWI “King's Cross” issue. Courtesy of the Simpson family.

The meeting was a disaster. Instead of easing the tension it only served to stiffen Mrs Simpson’s spine. She wouldn’t back down. On 14th November, making no mention of the Red Cross or Lady Young, she sent two packing cases to Buckingham Palace, filled with “shirts, pyjamas, bedsocks, pads, splints, nightingales, scarves & pullovers.”

Governor Young called it an “act of defiance.” Indeed, Trinidad was not Rhodesia.

What began as a folie à deux entered a new phase with the husbands, Sir Hubert Young, KCMG, DSO and Major G.H. Simpson, OBE, entering the ring, tag-team style, to take up the fight in defence of their wives. Forgotten was the war relief effort. It became simply a grudge match, a battle of wills. In an earlier day they would have settled it with pistols at thirty paces.

To use Lady Young’s term, yes, it was all “too stupid”. The only reason to mention it today is to shed light on a dynamic that is not well known – the animosity that existed between the white elite and the governor, not just Hubert Young, but all governors. As Sir Hubert put it:

“[T]he Simpson episode is not an isolated incident, or a question merely of discourtesy shown by a local lady and her husband to my wife and myself, but a symptom of a state of affairs in this Colony which has done incalculable harm in the past . . . There are in this Colony certain disaffected persons who are always on the look-out for an opportunity to take up an attitude of antagonism to the Governor . . . These are the people whose malicious unkindness to officials from overseas and their wives is a well known feature of social life in Trinidad.”

* * *

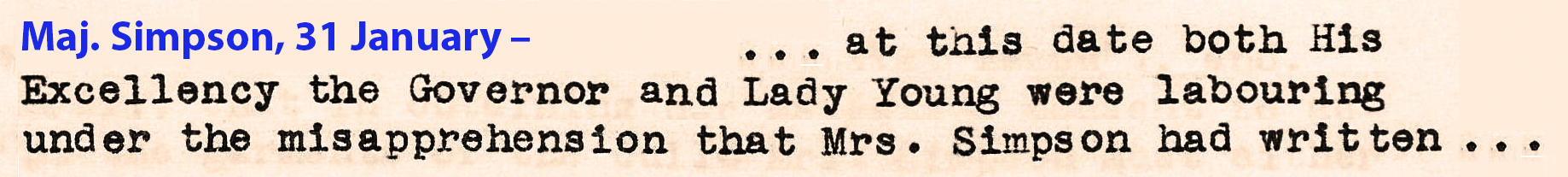

In early 1940 there came a major escalation of the dispute when the Simpsons decided to petition the secretary of state for the colonies for redress of their grievances, laying out the whole affair from their point of view. Governor and Lady Young rebutted the charges with their own version of events. As a result hundreds of pages of threats and accusations flowed from Port of Spain to London via boat, plane and wire:

It was against this backdrop of pettiness and spitefulness that Lady Young penned her infamous letter of 10th March.

The letter was widely shared in the colonial office – to the shock and alarm of everyone. Privately, the British officials may have agreed with Lady Young about the depravity and backwardness of non-white colonial subjects, but it was highly unusual to see something like that in print. Under Secretary of State W.B.L. Monson rushed to shield his boss from the scandal: “I feel that no comment on the substance of the letter can be made by the S. of S.”, he wrote on 15th April. The following day Asst. Secretary Harold Beckett spoke for the entire office when he wrote in his minutes:

“The fact that this is just an hysterical outburst must not blind us to the fact that Lady Young is saying what she really thinks. It does not make a very good mental background for anybody occupying the position of ‘lady’ of a West Indian (or indeed any other) Governor.”

At that point everyone in the colonial office piled on. On 16th April they called it a “lamentable story”; on 5th May it was a “ridiculous problem”; on 19th May a “very sordid affair”; on 23rd May an “unworthy little matter” and on 9th August a “petty and undignified dispute.”

As time dragged on with no response from Whitehall, Governor and Lady Young realised their support was slipping away. They became completely unhinged. On 3rd July, 1940 Sir Hubert wrote, in a desperate letter to the secretary of state, “They [the Simpsons] indulge in every form of slander and misrepresentation and also in victimisation and intimidation in some of their vilest forms.” Mrs Simpson’s entire family was “eccentric, self-willed, and well known for their intolerant attitude.” As for the tempest in a teapot created by his wife, he tried to inflate it into “an official matter of paramount importance to the successful prosecution of the war.” He even came up with a novel two-part theory to explain why Mrs Simpson had snubbed the Red Cross in the first place – first, jealousy (Mrs Simpson was supposedly “piqued” that she had not been appointed to the executive committee) and secondly, racial prejudice (she felt the Red Cross Society was “undesirably mixed” in terms of skin colour.) The latter charge was a real head-scratcher – of the twenty-nine people on the executive committee, twenty-six were white, two were Indian, and one was Chinese.

Finally, on 13th August, 1940 – almost a full year after the formation of the Ladies’ Shirt Guild – the secretary of state for the colonies informed Governor Young that Mrs Simpson had been cleared by the queen of any wrongdoing in writing to offer her assistance. It was seen as a near total victory for the Simpsons and a stunning letdown for Governor and Lady Young.

As for the tit-for-tat accusations brought by the feuding parties, the secretary of state would not dignify them by taking one side or another. Reminding everyone of the need to work together to win the war, he settled it in a single sentence: “I sincerely hope the whole matter will now be allowed to fall into oblivion.” It was like someone coming upon a carefully arranged chessboard and sweeping all the pieces off the table.

Somehow – hard to figure – Sir Hubert was allowed to remain in his post. What happened next, though, could not be pardoned – his refusal to go along with the occupation of the island by U.S. military forces in 1941. For example, when the U.S. Navy proposed Chaguaramas as the site of its operating base, Sir Hubert argued for another location – the Caroni swamp. (We all know how that worked out.) In early 1942 the colonial office recalled him to London, citing “ill health” as the reason. A bully had been out-bullied.

As the Youngs were packing their bags, an ambitious plan was being floated for a new highway connecting uptown Port of Spain with the Eastern Main Rd. Although a name was not really necessary at that point, it was announced that the roadway would be named for the wife of the departing governor. Perhaps it was in sympathy for all the abuse she had suffered. As a GUARDIAN editorial put it, “Firm, untiring, and constant, Lady Young has been a source of strength in the midst of many perplexities.” Many, to be sure.

Photo from the TRINIDAD GUARDIAN, 5th April, 1942.

Lady Young’s last day in Trinidad was 2nd April, 1942. As she walked to a waiting seaplane a photographer snapped a photo. On the left Governor Young looked like a cartoon version of a British colonial official – complete with bowler hat and walking stick. In the middle was Molly Huggins, wife of the colonial secretary, who was dressed more appropriately. On the right Lady Young was captured arching her back and clutching a briefcase. She appeared to be glowering at the photographer.

Before she got on the plane she was quoted as saying she “hoped that they might return one day on holiday,” but of course she had no intention of doing so. She hated Trinidad. In a place where many visitors were dazzled by the tropical sun, Lady Young saw only the deep shadows cast by it. She lived for another thirty-nine years, but she never set foot in Trinidad again.

Not even on 3rd June, 1959 – the day the Lady Young Road opened to motor traffic. It had taken seventeen years of digging and delay to create a paved path through the rugged terrain. In that period of time Trinidad had changed utterly. The power of the royally appointed governor had faded almost to nothing. A new group, the People’s National Movement, had won a majority in the legislative council. Mrs Simpson, in the first wave of white flight from the island, packed up her things (including a Cadillac automobile) and moved to South Africa. She died in Cape Town in 1972. At the ceremonial opening of the eponymous road the ribbon was cut by a Black man, Learie Constantine, the Minister of Works and Transport.

With the opening of the road, the term ‘Lady Young’ took on a new meaning that was kind of hard to describe. GUARDIAN staff writer Carl Jacobs (later editor) tried to explain it this way on 5th June, 1959, “long before Wednesday’s opening, the project had attained a secret glamour that might well have converted the name of Lady Young into an abundantly fascinating personality.” And so it was – Lady Young was transformed from a flesh and blood woman into a disembodied presence that guided motorists through the foothills of the Northern Range.